News for 10 August 2020

All the news for Monday 10 August 2020

Mandeep Singh becomes sixth Indian hockey player to test positive for COVID-19

Mandeep Singh is asymptomatic and is being treated along with the other five players in Bengaluru, where the national camp is due to start on August 20 at the SAI centre. - Biswaranjan Rout

Indian hockey team forward Mandeep Singh has tested positive for COVID-19, becoming the sixth national player to contract the virusmand, the Sports Authority of India (SAI) said on Monday.

The 25-year-old from Jalandhar is asymptomatic and is being treated along with the other five players by doctors in Bengaluru, where the national camp is due to start on August 20 at the SAI centre.

“Mandeep Singh, a member of the Indian Men’s Hockey team, who was given the Covid test (RT PCR) along with 20 other players at the National Camp at SAI’s National Centre of Excellence in Bengaluru, has tested COVID positive, but is asymptomatic,” SAI said in a statement.

“He is being administered treatment by doctors, along with the other five players who have tested positive.”

Indian captain Manpreet Singh and four other players had tested positive for COVID-19 last week after returning to the SAI Centre following a month-long break.

Defender Surender Kumar, Jaskaran Singh, drag-flicker Varun Kumar and goalkeeper Krishan Bahadur Pathak are the other four players, who tested positive.

According to SAI's doctors, all the players were showing only “mild symptoms” and are doing well. They are housed in the National Centre of Excellence in Bengaluru.

The players were earlier stranded at the centre for over two months (till June) when a national lockdown was imposed to contain the virus.

After coming back from the break, the players were in mandatory quarantine before resumption of training at the centre.

Sportstar

Expect fireworks at Razak Cup

By Jugjet Singh

THIS year's Razak Cup is expected to be an explosive affair as teams will feature Malaysian national players in the annual tournament.

In some of the previous editions, those in the national team were barred due to various commitments.

While the national men and women's teams have been given the green light to release their trainees for the Razak Cup, the men's junior players have yet to receive theirs due to the uncertainty of Junior Asia Cup dates.

The Razak Cup, on Sept 18-26 at the National Hockey Stadium in Bukit Jalil, will be the first local hockey tournament since the Covid-19 outbreak.

"Initially, I had wanted to field the juniors as a team in the Razak Cup," said national women's coach Lailin Abu Hassan.

"However, I did not get the Malaysian Hockey Confederation's (MHC) green light.

"It does not matter as my trainees, a combination of senior and junior players, are allowed to represent their respective state teams in the tournament.

"I believe it will be an exciting come-back to hockey following the Covid-19 outbreak."

The men's competition has attracted 15 teams while 11 teams will compete for the women's crown.

Players, officials and fans will have to adhere to strict Covid-19 guidelines during the tournament.

New Straits Times

'Thankless art that is best left uncomplicated,' PR Sreejesh on goalkeeping

Editor's note: Professional sport is as much a scientific pursuit as it is a recreational wonder. What appears routinely mundane is a result of the hours spent honing the craft and deciphering the body mechanics till it becomes a monotonous muscle memory. In Firstpost Masterclass, our latest weekly series, we look at precisely these aspects that make sport a far more intriguing act than we know.

Watching PR Sreejesh in full flight is an experience to cherish. The strapping Indian custodian, among the finest the country has seen in a decade at least, is a livewire on the turf who can be seen goading his defenders and effecting memorable saves under the bar with equal urgency. His quicksilver reflexes, expansive wingspan and fearless decisions have won India countless crucial games, and at his absolute peak, he was consistently rated among the best goalkeepers going around.

An affable man off the field, Sreejesh is a darling of the hockey-watching public across the country. In this edition of Firstpost Masterclass, he discusses the thankless art of goalkeeping, the technical components needed to excel at it, and the mental adjustments he makes during the game.

Tell us something about your childhood. What kind of kid were you and how did hockey happen?

I come from Kerala and hockey is not very big here. The state is known for athletics, and not surprisingly, I was drawn to athletics at school. I used to do long jumps, high jumps, shot put, races...everything. The competition was not of very serious nature though, it was more about having fun. When I was in the seventh standard, my PT teacher told me about the selection trials that were being conducted for sports school. On his insistence, I participated in the trials and got selected on the basis of my athletics' performance. I was quite a decent shot putter and had won a few state-level medals, but at the sports school, I realised that there were a number of shot putters in my age-group who were a lot better than me.

Coming from no sporting background, I thought it would be in my best interest to give up shotput and try something else. I dabbled in volleyball, football, and basketball, but was not comfortable. Kerala is quite good at all these three games, and the players, even at that age, could understand these disciplines way better than I could. Everything was new for me, whereas these kids had been playing their respective sports for a few years.

Then, I came to know that a few kids were learning hockey from a very basic level. That's when I thought of giving hockey a shot. My parents were very skeptical of my choice because back then in Kerala, even if you are good at hockey, there was not much you could do by way of making a career out of it. My parents wanted me to stick to volleyball, but I never wanted to go back because it felt awkward to play with the guys who knew the game whereas I couldn't do anything. I told my father, 'Give me three years. If I am not able to do anything in hockey, I will return to volleyball in Class 11 or 12.' That is how hockey happened.

Were you always into goalkeeping?

No, I started as a defender. At that age, more than the ability of the player, it is about how the player looks... so the bigger guys were put in defence, the lean, medium-built ones were in the midfield and the short, fast boys were deployed in the forward line. I was quite fat at that age and was of decent height, so I was slotted in as a defender. Then, in our age-group, it was customary for Class 8 boys to perform goalkeeping duties.

I was quite a lazy kid who didn't like to run around much. I had always looked at goalkeepers as happy souls who would just stand under the bar and do their thing. So, when the opportunity came, I accepted it with both hands. That's how my goalkeeping career started.

Goalkeeping is a tough art to master, and there is always this fear of getting hit. As a kid, how did you overcome this fear?

Yes, that was an eye-opener. I opted for goalkeeping thinking there's not much to do, but I realised it is completely different from how it may look from the outside. It is like you dangle chocolate in front of a kid before giving him/her injections. Goalkeeping is like that; it is a trap and by the time you understand that, it is too late because you are so invested in it.

Back when I started, we didn't have these latest pads. The pads we had were made of cloth and were quite heavy. I first started walking with them, then I wore them while working out, then I ran with them, and only after I was comfortable in them was I sent to the goalpost. That's when I knew that goalkeeping is a suicide mission.

'Overcoming fear simplifies goalkeeping.' AFP/File

At that age, people just smack the ball at you...they don't care if you get hit, or if they are aiming at the goal...they just hit it as hard as they can. For me, saving the goal became saving my soul and life. I told myself that I have to save the ball in order to save myself. So, I started blocking balls from my hands, like a football goalkeeper. I didn't use my legs often; instead, I would just dive and look to save from my hands.

Naturally, since my mindset was not right, I would concede a lot of goals. Then, my teammates began to tease me. They would say that they might as well place an immovable rock under the bar... those kind of things hurt you. It changed me, and I could actually feel the transition happening within me.

My seniors told me how to move and stand under the bar. I thought even if I get hit, I won't let a goal through. My coaches would give me examples of daredevil goalkeeping; they told me even if the opponent tries to kill you, you do not have to concede a goal. Those things pumped me up. At that age, all you want to do is impress your coaches. So, I began to put my body on the line. I got hurt a lot, but I knew I was doing it for the team. In doing that, I found strength and the fear went away.

Today, we use high-quality equipment and protective gear, but back then, there were no arm and thigh guards. The gloves we used were wicketkeeping ones and the pads were not great either. Our bodies were more exposed than covered. So, the players would target the exposed areas and it would really hurt. After every match, I would look at blue sore areas of my body, and after a point, I became numb. I couldn't feel pain anymore. After a couple of years when I moved to Class 10, I got better pads and things became easier.

Was there ever a moment in your career that told you that you're ready for international hockey?

No, no, that never happened to me because playing for India was not a thought when I started out. My biggest dream was to get into the district team and if everything goes well, maybe make it to the state team. In 2000, after the Sydney Olympics, athlete KM Beenamol and hockey player Dinesh Nayak came to my school where they were felicitated. I remember Beenamol tellng us, 'If I could play for the country, so can you.' That sparked a thought in the mind for the first time that maybe if I pay well, I can play for India.

Next year, I was selected for the Kerala Under-16 team and that was the time I travelled to Delhi for Nationals. My coach told me that the selectors will come to watch the matches and if I play well, I can make it to the junior national team. I was excited but didn't give it much thought. At that age, playing Nationals itself was a big deal. Eventually, since I was the second goalkeeper in the team, I never got a chance to play, but I was cool with it.

However, next year, when I played the junior Nationals, I was quite serious about making it to the national camp. It was, I think 2001, and I was in Class 10. I played really well and that paved the way for the U-16 national camp.

How was your senior India debut like? Do you remember that experience?

My first experience playing for India was in 2004 when I represented the junior team. I was in the camp in Chandigarh and we were preparing for a series against Australia. Our coach, Ramandeep sir, announced the team and my name featured in the list. We were given jerseys and I wore it and stayed in front of the mirror for two hours...I would face myself in the mirror, look at 'India' on the jersey, and then turn to see my name at the back... I don't remember how long I did that. It was a dream come true, a really special feeling.

My senior debut happened two years later at the SAF Games. Generally, we do not send our main team for SAF Games (now known as South Asian Games); it is generally the 'A' team that plays in this event. It was the same in 2006. The main team was preparing for the World Cup while another team was sent for this tournament. By that time, I was one of the main members of the junior team and a senior call-up was only a matter of time.

I made my debut in the final of the tournament against Pakistan and had a horrible match. In fact, it is one match of my career that I would like to forget. I conceded two goals between my legs and we ended up losing the match to our arch-rivals.

Goalkeepers, like wicketkeepers in cricket, are noticed more for their mistakes than their saves. What do you make of this?

When I started my career, my coach gave me a very valuable advice. He told me, 'Sree, you can become a hero of the game, or you can become the zero of the game. You are the one-man army on the field who can decide the match.' So, I knew very early in my life that goalkeeping, as you said, is a thankless job. It is a completely different game within the game.

A lot of times, teams score late goals in the dying minutes of the match and people end up blaming the goalkeepers. You must understand that goalkeeper is not the only person responsible for conceding a goal; it is a collective mistake. Recent studies have shown that there are at least five-six different mistakes that lead to a goal. Definitely, the goalkeeper is the final custodian, but it is always a team effort and people must understand that.

How do you get your focus back after you have conceded an early goal?

Whether you save a goal or concede one, you are playing a mental game. If I concede the goal in the first minute of the game, I have the next 59 minutes to think of that goal. Or, I have next 10 minutes to save a goal and rectify my mistake. Those 10 minutes can be very crucial. A lot of negative thoughts can bog you down: What are my teammates thinking? What will the coach say? What will the press write? What will the spectators say? Likewise, if you pull off a very good save, you can be on an emotional, self-congratulatory high for the next 10 minutes.

Neither of the two extreme emotions is healthy because you tend to lose focus. With time, you learn to stay neutral and balanced and focus on the moment.

'Conceding an early goal is tough, but it is important to switch off quickly.' Image courtesy: Hockey India

When I concede an early goal, I try to calm myself. I try to talk to myself a lot; I would say I am my best friend. The next step is talking to my defenders. I make sure they trust me because when a goalkeeper concedes an early goal, it can sink the morale of the team. So, I make it a point to communicate. That's how I get my focus back and get over the disappointment.

After this, I do another routine. I sing to myself, I look around the stadium, maybe smile and wave at the crowd, even look at a pretty girl. All of this helps me take my mind off the stress and helps me return to normal. So the next time ball comes in my half, I am ready. This entire process, though, is an individual thing. Each goalkeeper has his/her unique process depending on what works for them.

You come across as a very aggressive player on the turf, but outside the field, you are completely opposite. Do you flick a switch within you when you enter the field?

That happens subconsciously. If you alert your defensive structure and make sure they stick to the formation, you'll be able to keep the balls away. That's why you see me shouting at our defenders, to make sure they keep their structure and avoid balls slipping into my circle. Also, the defenders ask me to talk to them to keep them on their toes. VR Raghunath, I remember, used to always ask me to talk to him because that would keep him motivated. A lot of times I share some harsh words with the defenders, but there are never any hard feelings. It is only to keep them motivated and alert. That's an understanding we have developed.

You talked about switching on before a match. Yes, that happens with experience. It is different for different players, actually. Even after playing so many international matches, I have butterflies in my stomach before a game. That helps me realise that I am getting ready for the match; there's a lot of adrenaline. Then, when I enter the field, I know it is time to play my game. I try to get that 'game feeling' before and during the game, but you can't get it just like that. You have to practice that, and that's what I do during our training sessions.

Some people follow regimented routines on match days. They get up at a fixed time, have a certain fixed breakfast to keep themselves in that zone. For them, the preparations begin at the start of the day. I don't need that. I can do anything all day but when it's game time, I am ready.

When you are playing your first game, you don't know all these things. You need to try certain things, and after a fair number of trials, you come to a conclusion over what suits you. It is like shopping for a t-shirt, for example. You go across the store and pick, say, five t-shirts. You try them and then shortlist one or two. That's how it went for me. I tried various combinations for my matchday diet. Earlier, I used to eat a lot before matches, but that didn't help. Then, I mixed carbs and proteins on matchdays, but that didn't help either. I then switched to a protein-heavy diet, and that worked for me.

Some people develop this ability early. For example, Manpreet came to the national camp when he was 15, even before he made it to the junior team. He could understand these things very early since he was in the company of seniors at such an early age.

Do you visualise before a match? If yes, what is it that you visualise?

Yes, I visualise, but I don't do it before the match. I do it the previous night. I watch the opponents' videos; how they take the penalty corners, how they hit the ball, and so on. I visualise various scenarios, such as if they are going to hit the ball right down, how am I going to save, if I concede a goal, how am I going to recover; if I miss a save, how am I going to calm myself. I try not to dwell on the past. The idea is to feel something new.

It is believed that a goalkeeper is in the best position to control the game. Is it true? If yes, how do you actually do it?

That's true. Goalkeepers' vantage position does help them to monitor the game. A goalkeeper acts like a coach on the field. You have the responsibility to control the team and carry the defence because you have a better view of the game. To control the game, you need to have very good knowledge of the strategy. You need to understand your gameplans very well. You need to be at the players' meetings, attend their training sessions, understand what they are training for, and how, what skills they are looking to implement. These things eventually help you guide the players during a match and make full use of your position.

Why do you get into the bent, deadlift position when the opposition is approaching you? Also, are you looking at the ball, your defenders, or the opposition players?

We do that because that position helps you to stay balanced. If you look at tennis players, they get into a similar position while receiving a serve. It helps you move either way. While standing, we look to distribute our weight equally on both feet.

The rule says that you should look at the ball, not the player, but personally, I look at the ball as well as the position of the opposition players, especially if they are still quite far from me. Some players have peculiar skills, so you need to keep an eye on them. Some players may be good at hard-hitting, some like to slap the ball, some may be great at passing... so you try to see who is most likely to take the shot. That's why I do look at the players also.

I have developed this habit over the years and now my first instinct is to judge who is going to hit the ball, and then, I look at the ball.

You spoke about switching off and switching on on a matchday, but there's a lot of that going on in a match too. Sometimes the ball may not come in your half for a while and then there could be a sudden turnover. How do you manage such situations?

Yes, you are right. It happens a lot when you are playing a lower-ranked team; you dominate their defence and keep the balls in their half but suddenly one ball can come to you which you may or may not be ready to save. I think as a goalkeeper, you should train for such scenarios.

It is a mental game. The human mind cannot concentrate on anything for too long; our attention spans can be really short. So, it is important to distract yourself during the game when the ball is in the opposition half. If you try to focus for full 60 minutes, it will become very difficult for you. I would say it cannot happen. What I do in the middle when the ball is not near our half is quite similar to what I do when I want to refresh my mind after conceding an early goal. I sing to myself, wave at the crowd, look around. That is my way to switch off. As soon as the ball enters my half, my mind automatically gets switched on because it is fresh.

A lot of times we see goalkeepers rushing out towards the opposition players and then return to their spot after covering a certain distance. Do you have an area or a territory marked in your head, or is it just instinctive?

See, it is a very individual thing. Some goalkeepers are really quick on their feet and they are comfortable to come as far out as the top of the circle. Then, there are 'keepers with relatively slow reflexes. Such 'keepers generally stay in their position or do not go beyond five-six metres.

For me, I decide as per the situation. Most of the time, I prefer to stay close to my post, but if I see that there's a one-on-one situation developing at the top of the circle, I will definitely back myself and charge out because my one-on-one skills are better than my skills closer to the post. It is important to back your instincts and strengths.

During a goal-scoring move, there can be more than one opposition players inside the D. In that case, how do you decide whether to dive, rush out, or stand your ground, because there is always a chance of a rebound or a deflection?

It is difficult to explain, but as a goalkeeper, you must remember that all you have to do is react. Do not initiate the action. I always wait for the player to take the action and then react to it. Then, it also depends on who you are playing. Against a team like Australia or Belgium, for example, I know they will most probably hit towards the second post. A lower-ranked team, in all probability, will take a direct shot. That's always a calculated risk.

So as I said, in a one-on-one situation, I always like to charge out and kill the move, but if I see there are supporting players of the opposition around, I always stay back. The main target for a goalkeeper is to gain time in such situations. If you delay the situation, your defenders will come in and try to tackle the opposition.

At the end of the day, you just react. A lot of times, I end up thinking after I have done something, 'okay, how did I do that?' It is because it happens so naturally. I don't act just for the heck of it. I think, analyse, decide and execute, and this entire process comes naturally to me. It is a skill that comes with years of practice. I have been playing for India for over a decade, I have been in so many tough situations, and I have perfected my skills after practising them over 20,000 times, so for me, it just flows during a game.

How valuable is anticipation for a goalkeeper? Do you give it a lot of importance?

It is important, but not a pre-requisite. The job of a goalkeeper is to save the ball from sneaking into the goalpost. If you can anticipate well, that's an icing on the cake. I know people give a lot of value to it, but I have seen a number of goalkeepers whose anticipation goes horribly wrong and they end up conceding easy goals. The ultimate target for a goalkeeper, I repeat, is to save the goal. For that, you should look to get into the right position when the opposition player is taking a shot rather than you anticipating yourself and committing to a save.

Speaking for myself, I react to the situation. Some players follow a pattern, so you know what they are going to do in most situations. When you run towards the goal from baseline, you have two choices, to play a 90-degree pass or a 45-degree pass. When I see such a situation, I immediately check if I have a defender in the 90-degree area. If there's no one manning that part, I know that the opposition will pass there. In such a scenario, I wait and let them pass. Conversely, if I see there is no defender at 45 degrees, I commit and close down the move. So, it is a mix of anticipation and reaction depending on the situation. When the opponent is taking a shot, you forget everything and just look at the ball and react.

Let's talk about penalty corners. What do you discuss with the defenders while getting ready to save PCs? Also, what are you thinking when the drag-flicker is at the top of the D, about to receive the push?

With defenders, we always discuss the way we run. There are different ways of defensive running. You can have one, two, or three players running towards the ball; that is what a goalkeeper decides. I look at the opponents and analyse their attacking set-up, and based on that, I take a call on our defensive running.

The basic rule is to watch the ball at all times, but you do analyse the drag-flicker to get some clues about where they might hit the ball. You have studied the patterns in advance, and you know what a particular drag-flicker likes to do. If I am keeping to SV Sunil, for example, I know eight of his ten flicks will be on my right down because that is what he likes to do. I analyse all these things on video before the match. Secondly, I analyse myself. I look at where I concede more goals. If, for instance, I am weak on my right, I make a mental note that the opposition may target that area.

What we do in a match comes after lots of hours of practice. If you save almost 100 penalty corners each day in training, automatically you develop a sense of judgment. So, when the ball leaves the stick, we just watch and react without consciously realising. Wherever the ball is hit, I have to save it, that's what I eventually tell myself. After all these analysis and calculations, what I do at the end of the day is react to a drag-flicker's action. All my homework helps me make the correct decisions on the field, but at the core of it all, I just watch the ball and react. Plain, simple goalkeeping.

You said you back yourself in one-on-one scenarios during the match. By extension, do you enjoy shoot-outs too?

No, no, no... I do not like shoot-outs! I don't think any goalkeeper does. Shoot-outs are like ticking time bombs; you only hurt yourself. Even if you win one match in a shoot-out and lose the next, the entire blame will come to you, because it is between you and the opposition player. As a goalkeeper, I never want to be in a shoot-out situation.

'I back myself to come good in one-on-one scenarios.' Image courtesy: Hockey India

Can you take me through your process of gearing up for a shoot-out? What is your approach to such situations?

For shoot-outs, when I walk from the sidelines to the goalpost, I look at the player who will be coming up. Most probably, I would have watched his video in advance. I carefully study players during video analysis, see what position they play in, how they play, and so on. For me, in shootouts, it is all about killing time. I don't want to save the goal, I just go to kill those eight seconds. If I manage to do that, I know I'll save the goal by default.

When I reach the goalpost, I decide what I am supposed to do. I go through basics in my head, then, the whistle blows and I am ready. Once the whistle blows, I am done thinking; I just react.

Make no mistake, shoot outs are really tense affairs. Your adrenaline is high, the heart is pumping, but you have to keep calm. You have to think on your feet. It is not easy, but that is where experience comes in. I have been playing hockey for 20 years and I must have been in shootout situations 10-15 times in my international career. Earlier, my heart rate used to hit the roof, but with practice and experience, I am able to analyse and judge better.

Do you prefer to tackle reverse flicks during shoot-out by diving or by cutting angles?

It depends on the situation. I think I am comfortable both ways, moving with the ball as well as diving at the ball. I prepare for both situations, but once I am in the middle, I react to the situation. You cannot approach a shoot-out with a rigid plan. You prepare for everything, and then you are in the middle, you just use your weapon according to the situation. Most goalkeepers try to get their body in the line of the ball because when the opponent hits a reverse flick, he is targetting the net, and if you dive, you won't be able to stop the ball.

Generally speaking, I do not prefer to dive because when you dive, that is the end of your movement. That should be your last option. Your only objective to dive is to make a foul or clear the ball because if the ball is close by, the opponent still has a chance to score.

Can you briefly talk about your diving technique?

I follow a very simple technique to dive sideways. The idea is to transfer the weight to the side where you want to dive. So, if I want to dive right, I press my right leg and look to transfer my weight in that direction. The left leg is used to give a push. That helps you to cover some extra distance while diving. It is just like how a frog jumps.

You are one of the top goalkeepers of the world and teams do study and analyse you. How important is it for you to innovate?

You are right. With all the technology around, there are hardly any secrets, but I always look to change my style. I never try to play in the same way for a very long time. Having said that, there's a limit to how much you can change your game. I would not even advise changing your game a lot. Instead, you should look to consolidate your positives and work on your weaknesses while working on the opponents' strengths. Rather than worrying about what others are doing, you are much better off working on your game. That is the approach I have.

How is your workout different from other players? Can you take me through your typical fitness schedule?

Goalkeepers' workouts are quite similar to the rest of the teammates. We need aerobic strength, but not as much as other players. So, if they do 10 repetitions, we do six or seven, that is the only difference. We do more explosive workouts since we need more reactions and reflex actions. We train with the rest of the team, but the goalkeepers' group trains for specific movements. We start our workouts 10-15 minutes before other guys because we have to do targeted warm-up routines to get our hand-eye co-ordination going. We then pad up and join the team for some stability workout. Then, there are team drills and other stuff.

We eat and rest in the afternoon and hit the training again in the evening. On some days, we have gym sessions in the afternoon after training. Goalkeepers generally do not need heavy lifting but I prefer to lift a lot. I quite enjoy it.

Do you remember when were you first addressed as The Wall? How does this moniker feel like?

Being addressed as The Wall feels like a great honour, but for me, the title belongs to Rahul Dravid. He is The Wall. I remember it was after the 2011 Asian Champions Trophy win that some newspapers wrote that I am The Wall of India, and it got stuck. Sometimes, the recognition I get feels surreal. Fans love me across the country, chant my name, wave at me...it feels really special. At the same time, it gives me a great sense of responsibility too because I know they trust me to perform. It is a great feeling and it gives me the energy to keep performing to the best of my abilities.

Any advice for youngsters who want to take up goalkeeping?

Goalkeeping is a tough art. The only way to master it is to not overcomplicate. All I would like to tell youngsters is just stop the ball. Doesn't matter how, but first and foremost, just try to stop the ball somehow because that is what is goalkeeping. You can finetune your technique later. Secondly, don't be afraid of getting hit. Once you overcome the fear, things will become a lot simpler. So just go out and stop the ball and don't be shy to put your body on the line for your team.

Firstpost

Summer time means beach hockey time

It’s summertime in the northern hemisphere and many members of the hockey community will be heading to the beaches to enjoy some sunshine, sea and sand.

However, proving that hockey is a sport that can be played anywhere, on any flattish surface, beach hockey means that, even when on holiday, hockey players can still get a good practice session.

Beach Hockey is played within communities across the globe. Sometimes it takes the form of an informal get together with hockey-playing friends, sometimes it turns into a serious competition.

While it is easy to call a few friends together and play an informal game on a patch of sand, the KNHB, the national federation of hockey in the Netherlands, has published a set of rules and guidance for people looking to play beach hockey in a more organised and formal setting.

The pitch dimensions are 25 metres (goal ends) by 35 metres (sidelines), slightly wider and longer than one quarter of a regular hockey pitch. In front of each goal is a two metre zone, the equivalent of the circle. The goals themselves are four metres wide and two metres high.

There are also two 10 metre lines on each side of the pitch, measured from the goalie towards the centre.

Teams consist of eight players, with a maximum of five players on the field at any one time. One player can be nominated goalkeeper and have goalkeeping privileges, which includes stopping the ball with his or her hands. And players can be substituted at any time except during a penalty corner.

Hockey sticks can either be regular hockey sticks or adapted sticks – these have a larger head and three small holes that allow the sand to pass through. The ball is leather and slightly smaller than a football: it’s size and the fact it is softer than a hockey ball means it can be played in the air as well as along the sand, creating the opportunity to hone some great 3D and aerial skills.

The players play barefooted, but the rules state that a team must be wearing the same coloured tops, with the exception of the goalkeeper.

Goals can be scored from anywhere and the goalkeeper can use his or her feet in the two metre circle.

While Beach Hockey is a fun and informal way to keep up hockey skills while on holiday, many event organisers tap into its popularity to offer side competitors to enhance their main event. At both the 2014 Hockey World Cup in the Hague and the 2017 EuroHockey Championships in Amsterdam, Beach Hockey was a popular activity running alongside the main events. In the Hague, teams got together to compete on a social and ad-hoc basis, while in Amsterdam, competing nations were invited to send a Beach Hockey team to participate in an international competition.

In the Czech Republic in 2019, Beach Hockey was included in a festival of hockey organised by the Czech RepublicHockey Association and designed to present the ‘funky’ side of hockey to the city’s population.

One country where you would expect to find the sport being played is Australia. Long sandy beaches and a strong hockey culture would seem to be the perfect recipe for a tradition of beach hockey but the sport is played in surprisingly few locations: sharks and nudist beaches were both sited as reasons for not holding beach hockey events in the Northern Territory!

However, the sport has been a feature in other areas of Australia. A new beach hockey format is being worked on by the Douglas Hockey Association in Queensland, while in Tasmania, the activity is used as a promotional tool for main events.

The most active beach hockey-playing area is New South Wales. For eight years, until very recently, Cape Paterson, near Wongthaggi, was the venue for a thriving beach hockey scene. At one point, says organiser John Hackett, there were 14 teams playing a round robin league. The teams came from far and wide, with players travelling from Melbourne and West Gippsland – more than three hours drive away.

Hackett is hoping to revive the competition with a Beach Hockey Day during the summer, Covid-19 permitting. He says: “Cape Paterson at low tide is broad and long, with hard sand. After each game, we'd just move the pitch markers and little goals further along the beach. When we had 14 teams, we'd have seven games at a time; even at the end of the day, we'd have fresh sand for games. Everyone always enjoyed a body-surf afterwards.”

Proving that the surface is not too important when people want to get together for a game, Hackett also runs a 5-a-side hockey league on a tennis court in Wonthaggi. This has been running for more than 20 years and Hackett says hundreds of players have taken part, with many ‘graduating’ to play premier league and state hockey.

FIH site

The Mental Game: Motivate your field hockey pre-season

Sarah Murray

Pre-season training is upon us and with it the thought of no end of pain from various parts of the body that have not been used for several months. Cries of “I hate pre-season” “I wish we didn’t have to do this” “why am I here?” are frequently heard and that set me thinking about the psychology of motivation and its impact on performance as an athlete.

Motivation is a cornerstone for success in sport: if you lack the desire to improve in hockey then the other areas of performance (physical, technical, tactical, mental) are of no use. Motivation is what causes us to act, whether that means getting a glass of water or getting to a pre-season training session. To perform at your best on the pitch requires a process of continual progression and effort toward reaching goals: motivation is when a player WANTS this and WANTS to put the time in.

Take a moment to write down four things that make up your game as a player e.g. physical conditioning, mental preparation, great receiver of the ball or good at driving toward players.

If you look closely at the link between motivation and your performance in these areas you will see that motivation probably underpins each one.

Types of motivation

We are very different when it comes to what motivates us: not everyone has the motivation to turn up to the pitch 20 mins early to do some extra work on their drag flick, however, some do! As psychologists we usually categorise motivation into those players who are:

Ego oriented – measure their success on beating others and being the ‘top’ competitor, often rewarded by material goods/prizes

Task oriented – Measure their success by their own achievements and improvement.

Most of us will have both types of motivation but at varying levels which will be influenced by environmental factors. Generally the research shows that athletic performance is at its best when a player has either high levels of both or is low in ego and high in task orientation. This means that the player works hard to improve and will not give up if things do not go well.

Those players with high ego motivation and low task motivation are those that will not continue if they are not successful or possibly those who will not do pre-season training because they don’t WANT to – perhaps they perceive it gives them no reward or they fear potential failure and pain! Which type of motivation do you have most of and what can influence this for you?

Pre-season Grind

Pre-season training is referred to as the ‘grind’ or ‘foundations’. There’s no denying that it isn’t always pretty and it isn’t always full of enjoyment for many players. The grind often arrives in conjunction with hockey no longer being as fun as you remembered! It’s the point at which the endless fitness drills, basic stick work and throwing up on the side of the pitch can get tiring and a little tedious with seemingly no fun time in between (usually fun time for players equates to match play!) The truly task motivated players amongst you will see this as a great opportunity to improve and make a difference to your coming season. For others it is simply too hard and to refer to the earlier quote “why am I here?” The grind separates those who will make progress and will likely succeed from those who may not.

Here’s the good news………………..one of the best things about motivation is that it is a factor that you have total control over.

The player that chooses to motivate themselves for pre-season will have a greater chance of achieving their performance goals for the season, they will also experience greater levels of task motivation and more satisfaction with their own game.

This is why linking training to your goals is so crucial: pre-season is a vital PROCESS goal in order to achieve success on the pitch once the season gets underway. See my article in September 2012 Push for tips on setting goals.

MOTIVATION IS A CHOICE – TAKE CONTROL

All of us have an untapped energy source that can we can use to bring improved pitch performance. Enhancing motivation is essentially about a shift of attitude, developing a positive ‘can do, will do’ mindset and engaging in the short-term process goals that facilitate improvement.

Tips to recognise, accept and develop your motivation

- Motivational cues – a big way to stay motivated is through generating positive emotions associated with your efforts and achieving your goals.

- Set goals. There are few things more rewarding and motivating than setting a goal, putting effort toward the goal, and achieving the goal. The sense of accomplishment and validation of the effort makes you feel good and motivates you to strive harder.

- Daily questions. Every day, you should ask yourself two questions. “What can I do today to become the best player I can be?” and “Did I do everything possible today to become the best player I can be?” These two questions will remind you daily of what your goals are and will challenge you to be motivated to become your best.

- Self talk. The link between what you say to yourself about pre-season and how you are then motivated for it (or not) is great and one to be aware of. Recognise when you are positively framing the pre-season session but more importantly recognise when you are not, and understand how this may affect your motivation and therefore your performance.

Keys to pre-season

To be successful and cope effectively with pre-season training, you need to:

- Enjoy what you are doing by putting a positive spin on WHY you are doing it and focus on the improvements in your game and fitness at the start of the season because of it.

- Remember where you have come from. As you progress through the weeks of pre-season look back at how you felt at the start and notice improvements however small.

- Keep it all in perspective.

This article is from our archive

Help keep independent journalism alive in these uncertain times. Ahead of the new season, please subscribe in print or in digital format.

The Hockey Paper

India is not for sale: Ex-hockey coach recalls Dhyanchand's response to Hitler

His title of 'Wizard of Hockey' was also conferred by Hitler

Dhyanchand.

The date August 15 holds a great significance for every Indian around the world but 11 years before that day in 1947, the Indian flag flew highest in another part of the world -- Germany.

At the 1936 Olympics, the players of the Indian hockey team were creating an unbelievable sort of frenzy around them, courtesy of their performances in front of packed arenas of Berlin.

France felt the brunt of India's might in the semi-final, especially from Major Dhyanchand, who scored four of team's 10 goals to completely annihilate the European powerhouse. The stage was now set for India to take on hosts Germany on August 15. However, the mood inside the Indian camp wasn't that of excitement but of fear and anxiety. The reason being Adolf Hitler who was scheduled to watch the final along with more than 40,000 Germans.

Come the fateful day, Dhyanchand ran riot in front of the fuhrer, and what followed next holds much more importance that just an Olympic gold.

"It was Dada Dhyanchand, called the wizard of hockey, who in 1936 Berlin Olympics had scored six goals against Germans as India had won 8-1. Hitler had saluted Dada Dhyanchand as he offered him to join the German Army," former India hockey coach Saiyed Ali Sibtain Naqvi told IANS.

"It was during the prize distribution ceremony and Dada was silent for a few seconds, even the packed stadium went completely silent and feared that if Dhyanchand refused the offer then the dictator might shoot him. Dada had narrated this to me that he replied to Hitler with closed eyes but in a bold voice of an Indian soldier that 'India is not for sale'.

"To the utter surprise of the entire stadium, Hitler saluted him, instead of shaking his hand and said, 'German nation salutes you for the love of your country India and your nationalism.'

His title of 'Wizard of Hockey' was also conferred by Hitler. Such players are born rarely in centuries," he added.

Naqvi also gave an insight into what differences he finds in hockey of yesteryear in comparison to contemporary times. India is still longing to recreate their age-old performance, especially in the Olympics, and while there have been some encouraging displays, the gulf in class between the two different generational teams is clearly apparent.

"The Indian team at present is being trained and coached by European and Australians and now are playing in the European style. They have changed the entire concept of artistic hockey and mainly concentrate on physical fitness," said Naqvi, who also coached the women's team at 1978 Women's World Cup in Madrid.

"The Australian coaches try to teach them a combination of European and Indian style which is why they are successful. Though the present Indian team is young but their performances are not consistent. It has been observed in some important and crucial matches they have lost the game in dying minutes. The defence crumbles against the fast European teams.

"During my time the Indian team players were masters of their positions and carried great confidence. They were artistic dribblers, masters in different strokes and they had great national spirit to fly the tricolours in Olympics. Each player was conferred and can achieve top form.

"Old team had master penalty corner and penalty strokes specialists such as Trilochan Singh, R.S Gentle, Prithipal Singh, Rajinder Singh and MP Singh. For example, in 1956 Melbourne Olympics, R.S Gentle rightfully brought back victory through penalty corner against Pakistan. Similarly in 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Mohinder Lal scored through penalty stroke and India won the Olympics," the former coach added.

India are currently ranked fourth in the world following their string of consistent performances. They are now ready, according to Naqvi, to reclaim their throne at next year's Olympics in Tokyo.

"Yes, India is capable with young team led by Manpreet Singh as the captain. He is my favourite as well. It is expected that the team will be in the top four position. And the rest is on luck," the celebrated coach said.

The Tribune

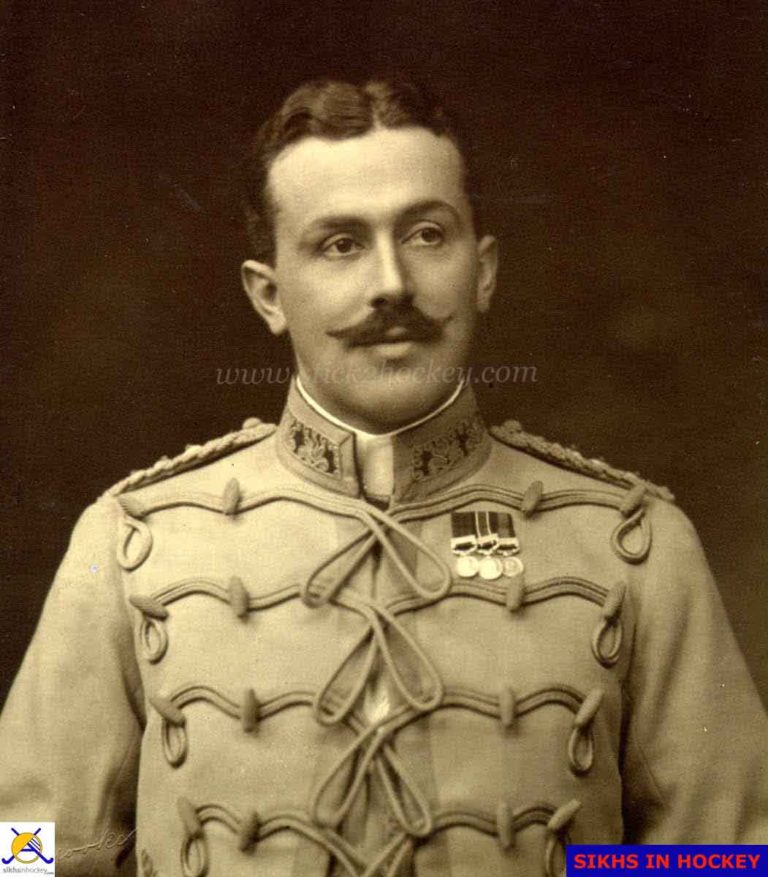

The first President of Indian Hockey Colonel Bruce Turnbull

The Scot in the Sikh Pioneers

By Dil Bahra

First president of IHF, Col Bruce Turnbull

It was a long mystery. Scarcely anybody knew of Col Bruce Turnbull, the first President of the newly formed Indian Hockey Federation (IHF). The formation of the IHF took place 95 years ago and was a turning point in the history of Indian Olympic Movement. Hockey historian and London based Dil Bahra takes us to unknown territory with his usual flair of prose, precise data, pathbreaking information and hitherto unseen images he painstakingly collected during his long research journey.

Bruce Turnbull was born in Khadki (formerly Kirkee) near Pune (formerly Poona), India on November 4, 1880. His father Peter Stephenson Turnbull was Surgeon Major General of the Indian Medical Service in Mumbai (formerly Bombay) in 1893 (also a fellow of the University of Bombay and Surgeon General with the Government of Bombay).

He was educated at Merchiston Castle School in Edinburgh from 1891 to 1896 where he played rugby and performed gymnastics. He enlisted at Royal Military College, Sandhurst, where he learned to play hockey which was a very popular sport there.

He was gazetted as an Under Officer into the Indian army as a 19-year-old on July 28, 1900.

Turnbull served with the 3rd Battalion of Rifle Brigade in Meerut for a year and on 19 October, 1901, was appointed 2nd Lieutenant in the 23rd Punjab Pioneers.

Seeing active service during the Waziristan campaign in which he did well, Turnbull was awarded the India Medal with the North West Frontier Waziristan 1901-02 clasp. The regiment became the 23rd Sikh Pioneers in 1903 and he experienced active service during the Tibet Mission that year and Colonel Sir Francis Edward Younghusband’s expedition to Lhasa in 1904.

He was awarded the Tibet Medal with clasp and was mentioned in despatches.

The 32nd Sikh Pioneers were also in this campaign and both regiments played hockey during this expedition.

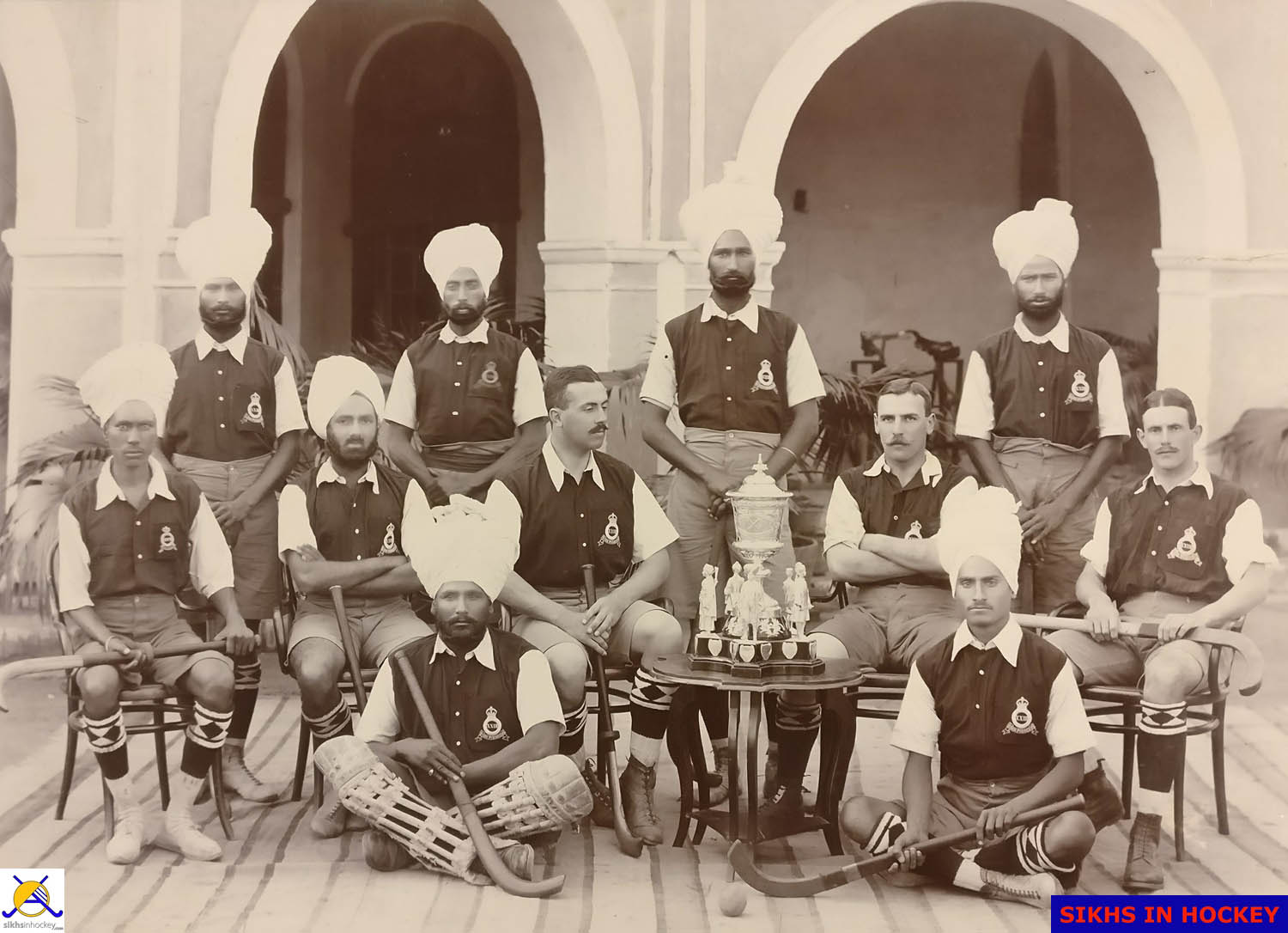

23rd Sikh Pioneers Hockey Team 1904 Bruce Turnbull is seated third from left

Turnbull played hockey for his regimental team and was one of three British officers who were in the 23rd Sikh Pioneers team that won the Punjab Native Army tournament on their return from Tibetto Jhelum in late 1904.

As a British officer in the Indian Army, he passed Urdu and Punjabi language examinations.

He saw active war service on the North West Frontier in 1908 with the 23rd Sikh Pioneers and was promoted to captain on 28 July, 1909. The 23rd Sikh Pioneers were based at Lahore Cantonment on completion of their NW Frontier tour. Turnbull was awarded the Indian General Service Medal 1908 with clasp for North West Frontier 1908. He was part of the 23rd Sikh Pioneers contingent at the Delhi Durbar in December 1911 and he was awarded the Delhi Durbar Medal. He was seconded as Adjutant of the 2nd Battalion, the Bombay, Baroda and Central India Railway Volunteer Rifles in India from January 1912 until 1914.

The Regiment served as mounted rifles and the 2nd Battalion HQ was at Ajmer. He was on leave in the UK at the outbreak of the Great War (WW1) in August 1914. He volunteered his services to the Army and joined the newly raised 7th Service Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders in Aldershot.

With the arrival of the Indian Army Corps in France at the end of September 1914, he moved to France and joined the 34th Sikh Pioneers (serving with the Lahore Division) on attachment on 14 November, 1914.

Turnbull was transferred to the 107th Bombay Pioneers for a short spell and went on to serve with the 15th and 47th Sikhs in France and Belgium. He was wounded near Festubert in France on 23 November, 1914 when he sustained a gunshot wound to his left jaw which required him to be transferred to a military hospital in the UK. He was with the 47th Sikhs during the second battle of Ypres, Neuve Chapelle in France on 26 April, 1915, where he was badly wounded in the attacks of the Ferozepore and Jullundur Brigades near St Jean. Wounded in the shoulder from a gunshot, Turnbull was admitted to a military hospital in the UK on 30 April, 1915, for a second time in a short spell.

Young Dhyan Chand in the 4th Battalion, 1st Punjab Regiment Hockey Team, 1923

He was promoted to major on 1 September, 1915. Having recovered from his wounds at Ypres, on 8 September, 1915, he was appointed Brigade Major of the 202 Infantry Brigade, a training unit based in Kent. He eventually re-joined the 23rd Sikh Pioneers in March 1916 as a Double Company Commander. The Regiment had transferred to Egypt from Somaliland in January 1916. In August 1916 he was appointed Brigade Major 20th Indian Infantry Brigade in Egypt. He spent a short period with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force until May 1917.

He returned to Sialkot, India, in June 1917 and was appointed as second in Command and Wing Commander of the 2nd Battalion, 32nd Sikh Pioneers, a new battalion raised in Sialkot in December 1916. He was mentioned in despatches in the London Gazette of 6 July, 1917.

He was then promoted Temporary Lieutenant Colonel and appointed Commander of the 2nd Battalion, 34th Sikh Pioneers on 2 July, 1917. He commanded the 2nd Battalion, 34th Sikh Pioneers in the North West Frontier in May 1919 during the Third Afghan War. The battalion returned to Sialkot in 1920 prior to disbandment in January 1921. In addition to the 1914 Star, War and victory medals, Turnbull was also awarded the Serbian Order of the White Eagle 5th Class with Swords.

Early in 1920, he went to the UK where he graduated at the Staff College, Camberley, UK in 1921. During this period he played hockey in London and the South East and also umpired hockey regularly during the season.

He then returned to India and re-joined the 23rd Sikh Pioneers on the North West Frontier as Second in Command, engaged in road construction in Waziristan. Turnbull was then awarded the Indian General Service Medal with Waziristan 1921-24 clasp for war services.

Indian Hockey Team at 1928 Amsterdam Olympic Games. Turnbull (5th from left)

He was appointed as Inspector of Physical Training at the Military Training Directorate Army HQ, India on 28 August 1922.

With this post, Turnbull also became the Honorary Secretary of Army Sports Control Boards India. On 3 June, 1923, he was promoted to Colonel. Turnbull was elected as the first President of the IHF on 7 November, 1925. He was on the Rules Board India and Referees’ and Umpires Committee in India.

He was the business manager of the Indian team which won the gold medal at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympic Games. Turnbull officiated at the Games and umpired the bronze medal match between Germany and Belgium.

Turnbull retired from the Indian Army on 20 June, 1926. Returning home to Scotland after his retirement from the Indian Army, he took up a position with the Edinburgh Education Authority in 1928, whilst also the organising secretary for Scotland on the National Playing Fields Association.

He also took command of the 4th/5thBattalion (Queen’s Edinburgh Rifles) The Royal Scots, a Territorial Army Battalion in 1928 and served until 1932. He was then appointed Commander of the 155th (East Scottish) Territorial Brigade in 1932 before finally retiring from the army in 1937.

Turnbull was appointed to the International Hockey Federation (FIH) Council on 23 May, 1928, and served on the Committee until 1932. He also served on the FIH technical committee from 1932 to 1937.

Bruce Turnbull (right) presenting trophies to the winning Edinburgh University team in 1950

He was elected President of the Scottish Hockey Association from 1935-37. Turnbull umpired regularly in Scotland, and at the Berlin 1936 Olympic Games he was appointed as a member of the Jury of Appeal and an umpire at the matches.

In 1935 he published the booklet ‘Hockey Hints’.

He was made a Deputy Lieutenant for Edinburgh in 1935 and was honoured with the CBE in 1937. Golf, gardening, and stamp collecting were Turnbull’s favourite pastimes.

He remained committed to hockey throughout his life. In 1950 he presented hockey trophies to the winning Edinburgh University team and in 1951 he was the Honorary President at the Scottish Hockey’s silver jubilee celebrations. His unsurpassed knowledge of hockey, both at home and overseas, made him a valuable member of the Rules Board.

He died peacefully at home on 21 January, 1952, in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Author DILJIT SINGH BAHRA sincerely thanks Dr Michael T R B Turnbull, grandson of Colonel Bruce Turnbull; Iain Smith, Editor and Archivist of The Sikh Pioneer and Sikh Light Infantry Association and Dr Tejpal Singh Ralmill of The Sikh Pioneer and Sikh Light Infantry Association for their valuable assistance in writing this document.

Stick2Hockey.com

Aleksandrov remains Russian Field Hockey Federation President despite embezzlement charges

By Liam Morgan

The Russian Olympic Committee (ROC) has confirmed Nikolai Aleksandrov remains the legitimate President of the country's hockey federation, despite the official facing embezzlement charges.

Aleksandrov was arrested last December on suspicion of committing economic crimes during his time as chief executive of Russian construction company Mosmetrostroy.

He was released under house arrest the following month before being detained on separate charges in April.

Aleksandrov was then placed under house arrest for a second time in May.

He is accused of concluding a fictitious contract and embezzling the funds from Mosmetrostroy.

The Russian Olympic Committee said the FHTR's elections held earlier this year were illegitimate ©Getty Images

The Russian Field Hockey Federation (FHTR) held an election in February following the criminal charges against Aleksandrov, where Andrei Kananin, an assistant to State Duma deputy Mikhail Buger, was voted in as President.

But the ROC has stated this election was invalid, according to Russia's official state news agency TASS.

"The February elections in the FHTR were recognised illegitimate, and Aleksandrov continues to be the head of this public organisation," the ROC told TASS.

"The elections were held in violation of the charter, since the current President, Aleksandrov, is alive and well and did not submit an application for his resignation.

"The terms of the charter have not expired at the time of the February conference."

The news reported in TASS is repeated in full on the official website of the FHTR.

The scandal surrounding Aleksandrov has also forced the postponement of the Russian national field hockey championship.

Inside the Games